The historic heritage of Waterford and the surrounding area is well known. The three forts, George Washington’s trip here, Pontiac’s Indians, the river traffic – all these give pride and silent reminder that the land is special. But there is more to a community than great historic events. When a local student, Malena Stiteler, became a National Merit Scholarship winner or Brooke Freeburg sets a county scoring record in basketball, and local elementary schools set State records in reading, everyone can take pride because everyone contributed to these success stories. When a local strongman, Harvey Wright, stands flat-footed, jumps up, and kicks out a light bulb eight feet off the floor, in the ceiling of Mitchell’s sawmill – it actually happened – we feel this warm awe. This is local pride – as old as recorded time. The following tales are not intended to be always serious, but to always look seriously at what we were and are.

Juva

On the map, it’s called Newman’s Bridge, the place where the Waterford-Wattsburg road crosses French Creek at the far eastern end of the township. The wooden covered bridge carried traffic for fifty years until in 1937 it was torn down to be replaced by an iron structure.

There was a cheese factory there. Karl Rockwood made a good many kinds of cheese to please the taste buds of his customers. One of the farmers, who at times sent over milk, was his sister’s husband, Glenn Steves. Ormsbee, Kimmy, Clute, Middleton, and descendants of the legend, Michael Hare, also did business there, especially when milk prices were down. The factory had an ice house where ice could be purchased all summer.

Two hundred yards north stood the Baptist Church, erected in 1860. It was the center of the community for one hundred years. Long ago, no one remembers when or even hearing when, a woman went to work in the country general store, a stone’s throw from the bridge. She ran the store and the post office but never seemed to have but one name, Juva. Where she came from no one knows. When people felt like congregating, they’d say, “I’m going down to Juva.” In this manner, the area got its name.

The beautiful valley is dead now – swallowed by a government dam. Juva herself disappeared as mysteriously as she arrived many years ago. There’s no trace that people lived and died there in that once beautiful valley. The primary pleasure in this area now are the eagles who nest there and the artists like Jack Paluh who are inspired by their beauty.

The Sentinel

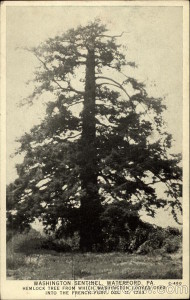

The great hemlock grew on the bank on the left side of LeBoeuf Creek, just up from the lake. Seneca Indians grew corn, beans, and pumpkins on the flats below her, while they  camped and built temporary homes on the high ground near the base. The French considered cutting the tree to get a better “fire pattern,” in case of siege – their fort was four hundred feet to the North, on an even higher bank. They decided against cutting it down.

camped and built temporary homes on the high ground near the base. The French considered cutting the tree to get a better “fire pattern,” in case of siege – their fort was four hundred feet to the North, on an even higher bank. They decided against cutting it down.

She saw the coming of the Virginian militiaman, George Washington, as he rode to the gate of the fort. He stayed as an honored guest inside the fort much of the next three days, before leaving to pave the way for future generations to settle in the valley.

Thirteen British marines, ten years later, escaped Pontiac’s Indians and the burning garrison through a drainage ditch that ran to the creek half-way to the base of the tree.

Having witnessed so much, later American honored her with the name, “Sentinel”. The early settlers gave her great respect. The high school yearbook borrowed her name, as did a local newspaper. By 1983, most people had forgotten why she was revered. In that year she fell, old “in the fullness of time”.

Louie Himrod

As a kid, Louie helped support himself and his family trapping on the Himrod lands across the flats between the Low Road and Donation Road. No fox, mink, or weasel was safe when he set his traps. The money-maker, however, was skunks – because there were so many of them. He caught hundreds! The business earned a lot of money but it cost him big time – he had to sleep outside the house in a shed or barn until the season passed. Louie learned early to survive in those hard times, in the years after 1890, when he was born.

As a young man, he went to work for the dairy across the tracks and mill race from the Waterford railroad station. He was their stationary engineer, keeping the steam engine running. They knew they had a man who could make-do. He produced parts, gears, you name it when equipment broke down. “Jack of all trades,” they would say.

He enjoyed being eccentric! When Alfred Himrod and his daughter Jean were working in the barn on the old Himrod homestead (where Carl Hunt later lived), Louie announced his arrival with an Indian war hoop, in the house, he’d whine like a dog at the door, ’til it was opened. He took no great effort to be clean or well-dressed – often his clothes were totally unkempt. After a short visit at the kitchen table, he’d rush to the back door to spit his tobacco juice over the railing.

When World War II was raging, Louie went to work for G.E. in Erie. Few people comprehended the complexities of winding an electric motor. He became a specialist and in a short time was training the new workers. He saw through complex problems, almost intuitively.

In his living room, he kept his planetary telescope, on the walls were maps of the heavens. He explained little-known terms such as “light year” or “planet” or “star” or “galaxy” to anyone who listened. He often mispronounced words, since he had never heard them spoken – for instance, he would say “Juniper,” instead of “Jupiter.” His information came entirely from reading and observing. All this from a man of limited elementary education.

Louie was a masterful gardener. For years, he raised vegetables for sale and “pick your own” strawberries. Once, when a patron who was picking berries complained about the number of mosquitoes, he called out, “If you women didn’t wear all that perfume we wouldn’t have the mosquitoes.” The ladies smiled to one another.

Louie was well read. He knew the history of the area, as well as the history of the country. He loved the land! He would tell of his ancestor, Simon Himrod, who immigrated to Bedminster Township, New Jersey; of Aaron who left New Jersey, settled in North Cumberland County, PA, with the Vincents, Boyds, Lattimores, Smiths, Lytles, Andersons, and Kirks; of how they came to know Martin Strong, William Miles, and Roger (John) Alden, of the Holland Land Company; and, of the migration of that great group to Waterford and Erie County.

Louie raised Shang (ginseng) beds and harvested the roots for market and export. Always, he carried great sums of money in an old salt sack, since he put no trust in banks. Truly a colorful, unique man, he died in 1969.

His son, William, lives on Cherry Street, in an attractive stone home that he built himself. It took four years, 20,000 field stones, tons of mortar, and hard toil to build the home he wanted. That kind of American “can-do” is learned, and William had an inspiring teacher.

Baseball

Before the war, every town and city in Northwest Pennsylvania had its baseball team or teams and they were all very good. Young boys learned the sport by shagging fly balls during batting practice and being “batboys.” When they were old enough and good enough, they filled in or earned their place on the field. While the players had great times and often joked and fooled around, the game was serious – you did your best to win. For over half a century, this was a “glue” that held a community together.

Waterford was among the best – maybe they were the best. The names and memories of the players still strike a warm spot around the coffee shops. The brothers Bud and Gene Mitchell were up there with the greats. They still recall the playing of Neil Bartholme and Merle Heard. “Remember when Hoot hit that home run,” it went up to the wooden part of the steeple on St. Peter’s Church.” Hoot Gibson hit a lot more than one – the rest did, too.

Nanny Whittelsey was a truly great ballplayer, the whole area for miles around agrees with that. He was a strong, well-built athlete, even in his advanced years. When he was well over fifty, he was still able to play with the best of them, and in his fifty’s he pitched a perfect no hit, no run game.

World War II changed town baseball as well as a lot of other things. The young men were called up. Everyone else worked a seven day week and often a twelve hour day. Travel was cut to a minimum. People’s minds were occupied with greater anxieties than sports. With peace, young men rebuilt their lives, while high school baseball came into its own.

Postwar Waterford baseball was marked by the coming of Carm Bonito, a no-nonsense teacher-coach from the high school. A player, coming back after striking out, was heard to remark, “That third strike was a bad call.” Carm got his attention, “If you’d hit the second strike over the fence, you wouldn’t have to worry about it.”

Red and Dell Shields, Tom Crocker, Chet Russell, John Senkalski, The Owens’, the Peters’ Dean Scott, Bill Powell, Dick Fuller, – the list goes on and on. Al Rinderle was a professional quality shortstop and Fran, his brother, could and did play any position, as well as pitch. Waterford High School can be proud of this era.

Let’s consider one game – Wesleyville, at Wesleyville on April 23, 1953. “Koko” was catching (the scorer could not spell “Couchenour”). Bill Skiff was pitching. The usual “no run” defense was behind him. It was a windy day, warm and dry, with little spirals of dust rising up like miniature hurricanes and blowing in from the outfield. The Wesleyville team was accustomed to hitting the long ball and scoring quickly and often.

| Inning one | Waterford | 4 runs |

| Wesleyville | 3 strikeouts | |

| Inning two | Waterford | 4 runs |

| Wesleyville | 3 strikeouts | |

| Inning three | Waterford | 0 runs |

| Wesleyville | 3 strikeouts | |

| Inning four | Waterford | 0 runs |

| Wesleyville | 2 strikeouts – pop-up to first base | |

| Inning five | Waterford | 3 runs |

| Wesleyville | 3 strikeouts | |

| Inning six | Waterford | 0 runs |

| Wesleyville | 2 strikeouts; walk-thrown out at 2nd base | |

| Inning seven | Waterford | 0 runs |

| Wesleyville | 3 strikeouts |

Against a very good team, a perfect game! No hits, no runs, no errors, 11 runs, and 19 strikeouts in a seven-inning game. Outstanding!

The 1953 record was 14 wins, 0 losses, and three no-hit games – two by Bill Skiff and one by Chet Russell. They were Erie County Champions. Erie County winters are easier to bear with memories like these.

Old Mossback of Lake Le Boeuf

“He was eight feet long and every inch a fighter,

Eighty pounds of mean and ornery pike.

The Frenchmen couldn’t catch him and the English wouldn’t try;

And the Seneca claimed that fish would never die.”

From the “Ballad of Old Mossback,” by James Skiff, whose great grandfather caught many giant muskies at Lake Le Boeuf

Chet Semour is the only man who ever actually hooked Old Mossback and survived to this day to tell about it. He was fishing in – lets start at the beginning.

Lake Le Boeuf is fed by three main streams – Le Boeuf Creek, Boyd’s Run and Shaw Run that feeds the adjacent “Hidden Lake.” Setting on the edge of Waterford, it has been a fishing paradise since the Indians and then the French and then the English came to claim and conquer the land – long before the Americans. Muskies thrive in the unique environment of the small lake; only Chautauqua is competition.

Chet and his brother, Ted, were fishing between their grandfather Chet Comer’s livery and the island, when Old Mossback came up from under his boat. Fear set in that the boat would overturn in its wake. The fish was way in excess of five feet and was close to seventy pounds. Then it struck! The line pulled ’till the reel literally smoked. Then, after diving deep into the seventy foot depth, the fish went high into the air, convulsed its body, and spit the plug far across the bow of the boat. That incident in the 1930’s was the last reported sighting of the creature.

Sitting and drinking his morning coffee, Chet spoke almost reverently about Old Mossback. Others, listening to their friend’s experience, added other incidents about the uncanny wisdom, even intelligence, of the monster. All agreed, he was “too smart” to ever get caught. The lake keeps its secrets.

One of the men, an old time fisherman who enjoys great respect from the group, quietly talks about his repetitive dream that comes just before sleep. In semi-dark, the old muskie hits his plug, the battle begins, man against his protagonist, reel him in, let him run, reel him in. Always in the end, Old Mossback slips away but the fisherman knows he’ll return. In his life the conflict is never-ending.

Old Mossback was never framed and hung on a wall; the aging fish was crafty and snarly. Maybe he learned some lessons living with the older bones beneath the surface.

Lake LeBoeuf, named by the French mapmakers after water bison which once existed on the shores, was Old Mossback’s kingdom; his preferred hideout was an old sandbar, according to the tale among anglers. Muskies are known to be territorial and solitary and can live to be 20 years of age; Mossback must have been one of the elders. He thrilled and eluded the muskie hunters of the late 1930’s and well into the 40’s and maybe even the fifties.

Reginald C. Exley, Sr., was one of those muskie hunters. A resident of the borough Fairview, twenty miles to the north, he also served as that community’s mayor. On his way to the lake, he likely drove past the statue of George Washington, dressed in a British military uniform, on a small island in the middle of the Waterford’s main highway, State Route 19.

The statue was erected (1922) to commemorate his visit to the old French Fort LeBoeuf on the shores of the lake in 1753 when he was still a British officer. Washington’s visit was to get the French to move out of territory claimed by Great Britain; the diplomatic mission failed and hostilities soon broke out the French and Indian War. The unique statue, the only one depicting Washington in a British uniform, was later moved off of the highway (1945) and placed in a small park close to the lake where it still stands.

Exley was captivated by the thought of landing Old Mossback, said to be over five feet and more than fifty pounds; the stories claim he was the meanest fish ever born. Exley first experimented first with live frogs in homemade nets. As a frequent and avid muskie hunter, he was aware that the bullfrog was the meal of choice for the fish. The effort proved to be an unsuccessful venture.

Exley then decided to carve out of a chunk of an old telephone pole an artificial bullfrog. Exley eventually created a set of two metal wings on either side of the lure to give it the movement and action similar to the plentiful bullfrog population in the lake. The wooden lure was painted to look like a bullfrog and Exley began to catch more muskie than before. The famous LeBoeuf Creeper, the original bullfrog muskie lure, soon became the lure of choice throughout the region.

LeBoeuf Creeper

Eventually, the first wooden LeBoeuf Creepers were produced at the LeBoeuf Bait Company and years later were made of plastic in two different sizes at several locations. They were a popular lure sold in hardware stores and bait shops throughout the small villages of the area; places like Union City, Mill Village, Edinboro, and Wattsburg.

Many muskies were caught using the creeper lure, the framed pictures have many stories; other lures are reported at the bottom of the Lake LeBoeuf, the spoils gained by a successful muskie. These are artifacts now as well.

But Old Mossback was smart (or really lucky) and was never captured; he likely died near his lair, without any public flair. Exley died of heart attack a few years after he created his homemade waddling bullfrog lure, although, as the story goes, he did have some respectful and fearsome strikes from Old Mossback.

For several reasons, including patent disputes, the famous LeBoeuf Creeper was discontinued in the 1960’s; no longer produced, it is more of a collector’s item today, an artifact from another era. An occasional lure can still be found at a garage or estate sales, hidden in some long-ago tackle box, some maybe at the bottom of the lake. No one knows for sure exactly what’s beneath the surface, except for Old Mossback.

Thank you to Lewis Dove, Fort Le Boeuf School District teacher (RIP) , who furnished the above information. Mr. Dove has written many booklets and books about the history and people of Waterford.