Fort LeBoeuf French Indian War Museum

South of the Judson House is the Fort LeBoeuf Museum. Built on the site of the original French fort, this modern building includes numerous exhibits on the Indians who lived here, the French and British fur trade, and archaeological excavations of the site that was conducted by Edinboro University. The Museum is open for touring. See the sidebar for hours of operation. Groups tours by appointment. Admission is free, but donations are accepted and appreciated to help maintain the museum.

In 1753, the French invaded the southern shore of Lake Erie, building four forts to seal off the English settlers who were attempting to occupy the Ohio frontier. The first bastion on the lake at Presque Isle (Erie) was quite substantial; it was positioned to repel the English coming from east through the Finger Lake region. It was built to withstand an army, assuming they had no heavy artillery.

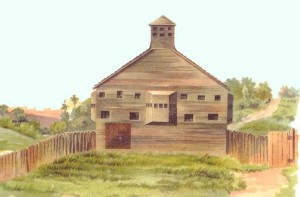

The two interior forts at Fort Le Boeuf (Waterford) and Machault (Franklin) were designed to protect against raiding parties and used primarily as staging and warehouse depots, but planned in the European style and could not have been taken by anything but a massive effort on the part of a well-supplied army. Both were manned by a minimum of 150 men.

The two interior forts at Fort Le Boeuf (Waterford) and Machault (Franklin) were designed to protect against raiding parties and used primarily as staging and warehouse depots, but planned in the European style and could not have been taken by anything but a massive effort on the part of a well-supplied army. Both were manned by a minimum of 150 men.

Duquesne, at the “forks of the Ohio,” was built to receive and repel the serious attacks of the British. The French policy in North America was to take from the continent the raw materials it wanted – furs, fish, lumber – without building great cities, or areas of manufacturing, or even developing much agricultural land. Trade goods necessary to keep the Indians satisfied and friendly were produced in France and transported to North America. By 1753, the French had befriended the Indian tribes (all except the Iroquois), and through their trade, had destroyed the aborigine way of life. The rifle, powder, lead shot, steel traps, knives, axes, needles, and a hundred other things – including alcohol – had made the Indian totally dependent upon the European. The old ways were forgotten – survival depended upon trade. Official French policy also dictated that the traders remember that the Indian owned the land. Clothing, trinkets, ribbons, beads – these things were given as a right to cross a tribe’s land or for the right to trade. The Frenchmen understood this principle. From the French forts and towns came a flood of guns, knives, tomahawks, and other goods that kept the Indians on their side. The French told the Indians that the English meant to take the land – for themselves. Conflicts between the two powers finally escalated into open warfare in 1756. With their Indian allies, the French were initially successful – they learned to fight the “Indian Way,” which was by stealth, surprise, ambush, and frightening terror. With the encouragement of France, the Indians began a policy of attacking English or American settlers who were starting farms on the frontier. This stream of settlers from the East into the valleys of Western Pennsylvania and Virginia was virtually stopped; their settlements along the Ohio burned; they were brutally tortured, killed, scalped, and their bodies were mutilated. All this with French encouragement.

Thoughtful older chieftains were divided in their opinion between supporting the French or the English. Then, in 1759, six years after they invaded the Ohio area in force, the French were defeated – totally, not only in the Ohio, but west of the Mississippi and north to Hudson’s Bay. The French were done. The war between the two powers continued in Europe; there it was referred to as the Seven Years’ War; but in North America the war between the superpowers was over. They destroyed Duquesne and burned Machault, LeBoeuf, and Presque Isle. In 1760, England’s Colonel Bouquet rebuilt Duquesne (Calling it Fort Pitt), Machault (calling it Venango), LeBoeuf, and Presque Isle. Fort Pitt became a first-class fortress, and Presque Isle was built as a strong garrison fort, while LeBoeuf, and Venango were not as well planned or provided for. There appeared to be no reason to build powerful forts – what could “savages” do to disrupt a strong English military? The three upper forts were manned by small garrisons of Royal Americans, poorly trained and disciplined, with one officer in charge. When the Indians attempted to make peace with the English, they were confronted by an arrogant officer who had a single purpose – destroy the “savages!” In 1763, General Amherst sent orders to all British garrisons to slow the flow of rifles and powder to Indians. Knives and traps could be traded for furs, but only enough powder to replace that which was used up in hunting could be provided. The result of this edict was that the cost to the Indian for manufactured goods went up four times the “old” rates. This highhandedness enraged the tribes. Into the mix steps a man of organizational genius – Pontiac. This Ottawa Chief from the Detroit region realized he needed to organize the tribes of the Northwest Territory by convincing them that the English wanted their lands and also wanted the Indians dead! He planned a series of attacks on thirteen English forts which he planned to take with minimum losses; the absolute brutality and cunning used against the enemy, he thought, would cause them to sue for peace. Of the thirteen forts he sent warriors to attack, nine fell.

| 1. LeBoeuf | (Waterford, PA) |

| 2. Presque Isle | (Erie, PA) |

| 3. Venango | (Franklin, PA) |

| 4. Pitt * | (Pittsburgh, PA |

| 5. Niagara * | (Youngstown, NY) |

| 6. Detroit * | (Detroit, Michigan |

| 7. Sandusky | (Sandusky, Ohio) |

| 8. Miami | (Fort Wayne, Indiana) |

| 9. Adenine (Wy-ah-tee-non) | (Lafayette, Indiana) |

| 10. St. Joseph | (Niles, Michigan) |

| 11. Edward’s Augustus + | (Green Bay, Wisconsin) |

| 12. Michilimackinac (Mish-ill-lah-mach-in-naw) | (Mackinaw City, Michigan) |

| 13. Sault Sainte Marie | (Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan) |

| * Was not overran | |

| + Was evacuated |

Approximately 450 soldiers and civilians in the forts were defeated, massacred, and scalped or otherwise mutilated. In the outlying areas, hundreds of settlers died at their hands. The Indian’s losses? Not a single death. (Records on both sides are sketchy as to Indian casualties, but all authorities agree, the Indian losses, if any, were few in these nine attacks.) Only Detroit, Pitt and Bushy Run did the warriors suffer significant losses. The attacks on Venango, Presque Isle, and LeBoeuf were typical and reflect what had been done at Forts Sandusky, Miamis, St. Joseph, Michilimachinac, Edward’s Augustus, and Ouiatenon. Remember: the original Americans were “individuals”; European stock has only a poor understanding of this term. The very idea of “storming” an enemy in his fortress was unthinkable. The warriors were simply not expendable. The Chiefs would not order such action, and the warriors would not obey. On June 13, 1763, Lieutenant Francis Gordon was in charge of Fort Venango. The trooper on duty at the gate called out that a party of twenty-five Swanees and Senecas led by Chief Kyashuta, a Seneca, was coming from the west on the Cuyahoga Trail. When they reached the gate, Lt. Gordon greeted them. The Chief asked for a council. Indians used this method of “breaking the ice” – a little tobacco, some small talk, then business. They were invited into the fort. While Gordon and the three Chiefs entered his chambers, the other Indians joked and talked with the soldiers and sided up to the troops. At a signal, they pulled their knives and tomahawks; in less than one minute, all 15 of the soldiers were on the ground, dying, and scalped. Lt. Gordon was led out of his quarters with a rope around his neck. Paper, ink, and a table were put in front of him as Kyashuta dictated a “confession” for him to write. In it he “admitted” to the truth of the grievances of the warriors. They included the refusal to trade for guns and powder, the refusal to close the frontier forts as promised, and the arbitrary dealings they received from General Amherst. He signed the paper. Then the torture began! In Europe, when a man, woman, or child was burned at a stake, the victim was tied tightly to a post and brush was piled up against them. The fire burned their flesh and they soon inhaled the flames, searing their lungs; death came from a combination of shock and suffocation. Many thus died at the orders of their Church and government. The Indian way was different! Lt. Gordon was led – crying and begging – to a post. A rawhide rope was tied to one wrist and the other end to the post approximately eight feet above the ground. He could move back and around the stake about five feet. A brush fire was started at the base of the post. When the Chief was ready, he started to torture by cutting into Gordon’s flesh with his knife. The screams of the victim gave the young warriors great pleasure, and they then took their turns. They smashed his toes, burned him with hot embers, cut off his ears, blinded him with hot sticks, and in every conceivable manner, caused him to suffer. This went on for nearly two days! It was in this position he was found a few days later – beheaded! Ensign John Christie was in charge at Presque Isle. He had 27 men and one woman in his garrison. She was the wife of one of the men. Christie lived to tell how the fort fell – full of fight, glory, and heroic deeds. He said the Indians built breastworks and dug tunnels to attack, after losing many men in trying to charge. He reported that the enemy suffered many losses. When English troops viewed the scene later they weren’t so sure that Ensign Christie had given an accurate description. The massacre was too complete and there were no signs that the Indians had suffered any losses to support the Ensign’s story. The Indians themselves said they suffered no losses at Presque Isle.

Laura Sanford’s, History of Erie County, a well-researched early presentation of the area, offers a different version, much more in keeping with Indian attacks at Forts Sandusky, Miamis, and Michilimachinac, and, of course, Venango. Indian custom made it unthinkable for warriors to attack an enemy on another tribe’s land unless a warrior chief of the home tribe led them and was, of course, given first pick of the spoils. Kyashyuta, a Seneca, who left the torture of Lt. Gordon to the younger braves, hurried northward to the shores of Lake Erie and met the warriors from the west in time to defeat the troops at Presque Isle. They then proceeded to Fort Niagara. However, Niagara was forewarned; the Indians were not successful there. When Colonel Bouquet was informed of the defeat at Presque Isle, he hoped aloud that Christie was dead – otherwise, he would be tried and hanged. To lose such a well-built fort that he had personally planned was criminal. Christie was court-martialed in 1764; his aide in 1766. He gave the description previously mentioned; his aide two years later supported that story, and lacking any other witnesses, they were not punished. The garrison of thirteen Royal Americans and Ensign George Price at Fort LeBoeuf were not aware that Venango had been taken. They had had a warning that they could expect trouble; the forts in the west had fallen. But no extra security was taken at Fort LeBoeuf. On June 18, Price became concerned when he realized five Senecas were inside his stockade talking with guards – and the men were not even armed! The Indians seemed cordial and asked only to be able to cook their food and rest inside the gates. Price granted the wish. They left and returned a little later (about noon) with twenty-five more warriors. The main defensive structure at LeBoeuf was a log building, two stories high, with plank floors. It measured 24′ by 32′ with one door in the middle of the front side. Small windows with shutters let in light and allowed soldiers to fire upon an enemy. In the back, portholes for firing guns were provided, and there was one small window too small to enter or exit. Ensign Price assembled his 13 men in the building. The Indians wanted to borrow a kettle, but it would not pass through the window. He refused to open the door as they demanded in order to pass out the pot. The warriors went to an adjacent building, tore off some planking at the sill and removed some stone foundation, and from their protected position they were ready to fire on the troops. At evening the battle began. No one on either side as hit by the firing of the guns, but the soldiers were in a bad predicament. By ten o’clock the Indians shot flaming arrows in the wood shingles, setting them ablaze. By midnight, the situation was hopeless – the roof and upstairs were aflame and burning embers were coming down on the men. The Indians knew (or thought) that the men had to exit from the front so they ignored the back of the building. By tearing off the planks lining the window, the 14 men escaped the building, unobserved, and fled into the woods. The Indians assumed the fire had consumed them. One of the men, John Dortinger, had been stationed at Le Boeuf for two years. He said he could lead them to Venango. From midnight to dawn he led them through swamps and creeks – a distance of 20 miles or so. Six men became separated from the group. At dawn they saw smoke in the distance – it was Fort Le Boeuf! One of the men punched Dortinger, splitting his lip and knocking out a tooth. They started off again at about 11:00 a.m., on June 19th, and unable to locate the lost men, they undoubtedly stayed close to the Old French Military Road that led overland directly to Venango. On June 20th Price and his party of eight arrived at Venango. They cut the mangled and burned body of Gordon from the post and laid it by his dead comrades. They arrived at Fort Pitt on the 26th; four of the lost soldiers came in later. The other two apparently died. All in all, the little detachment at Fort LeBoeuf was very lucky. The end of Pontiac’s campaign came late in 1763 when the tribes, one by one, deserted him. They had not been able to take Forts Pitt, Niagara, or Detroit. The hope of getting aid from France collapsed with the treaty of peace ending the Seven Years’ War. With winter coming, they were unable to carry on a long, protracted war. Pontiac continued trying to attract allies to his cause. He simply could not command a following among the discouraged tribes. The Ordinance of 1763, protected Indian lands for a time, and a Revolution gave people something besides westward expansion to worry about. In 1769, a young follower tomahawked the old warrior, forever ending his conspiracy. The ruins of Forts LeBoeuf, Venango, and Presque Isle lay deserted for thirty years. In 1796, a new army came through, totally destroyed the Northwest Indians all the way to the Mississippi. The American flag was raised over the land once dominated by the French and English. American forces protected settlers at Presque Isle, LeBoeuf, and Venango. So what is the legacy of Pontiac? A frontier farmer in central Pennsylvania whose family had been massacred by Pontiac’s followers remarked: “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.” This became the official policy of the new government for more than a hundred years, and the separation of the races remains a national problem even to this day.